Out of the Mire

…because thriving is the goal

Mindfulness and Your Thoughts

Here is a powerful idea:

Your memories and damaging thoughts are like propaganda. They are not real. They are not you.

To quote Rhett and Link from Good Mythical Morning, let’s talk about that.

Why is it so hard to get a hold of our own minds? Why are we run over by our emotions, moods, and thoughts? Why are cognitive distortions such a problem? This is why:

- when you start to feel a little sad, anxious or irritable, it’s not the mood that does the damage but how you react to it.

- the effort of trying to free yourself from a bad mood or bout of unhappiness—of working out why you’re unhappy and what you can do about it—often makes things worse. It’s like being trapped in quicksand—the more you struggle to be free, the deeper you sink.

“When you begin to feel a little unhappy, it’s natural to try and think your way out of the problem of being unhappy. You try to establish what is making you unhappy and then find a solution. In the process, you can easily dredge up past regrets and conjure up future worries. This further lowers your mood. It doesn’t take long before you start to feel bad for failing to discover a way of cheering yourself up. The “inner critic,” which lives inside us all, begins to whisper that it’s your fault, that you should try harder, whatever the cost. You soon start to feel separated from the deepest and wisest parts of yourself. You get lost in a seemingly endless cycle of recrimination and self-judgment; finding yourself at fault for not meeting your ideals, for not being the person you wish you could be.” (Mindfulness: An Eight-Week Plan for Finding Peace in a Frantic World)

Let’s stop here. In the process of trying to solve our emotional distress, thoughts emerge. Recall what I’ve been posting about core beliefs. This is when those core beliefs come into play. Let’s look at an example.

When I was living in France, I lived directly next to another American named Liz. She was the most even-tempered person I think I’ve ever met. We became fast friends and traveled everywhere together. She was never in a bad mood. She always seemed happy. I have rarely met anyone like her. One day, however, she returned with a test in hand and tears on her face. She had failed an exam, and the teacher in characteristic French fashion had shamed her with one eloquent sentence on the test: “Il faut essayer un peu,” meaning “You have to at least try a little bit.” Ouch! I waited for her to explode or lie in bed for days questioning her existence or capabilities. She had studied. I took the same test. We studied together. Nope. It never happened. Why?

She didn’t have any negative identity-based core beliefs. She had a good childhood and adolescence. She didn’t have abuse in her background. She didn’t really tie performance to identity. She hadn’t experienced trauma. She was very fortunate. She felt the sting of the shame and the immediate failure, and then, lo, she moved on. She self-regulated.

The idea that we can experience an emotion and not fix it but simply allow it to pass might be a new idea. You can wake up in the morning with mild anxiety and simply allow it to exist without asking repeatedly, “Why am I anxious? When did I feel this way before? What is this about?” but instead begin to recognize that you are not your anxious feelings might feel like a non-option. Aren’t we supposed to chase down every negative emotion and solve them? Well, as studies are beginning to reveal, we aren’t actually solving anything:

“We get drawn into this emotional quicksand because our state of mind is intimately connected with memory. The mind is constantly trawling through memories to find those that echo our current emotional state. For example, if you feel threatened, the mind instantly digs up memories of when you felt endangered in the past, so that you can spot similarities and find a way of escaping. It happens in an instant, before you’re even aware of it. It’s a basic survival skill honed by millions of years of evolution. It’s incredibly powerful and almost impossible to stop.

The same is true with unhappiness, anxiety and stress. It is normal to feel a little unhappy from time to time, but sometimes a few sad thoughts can end up triggering a cascade of unhappy memories, negative emotions and harsh judgments. Before long, hours or even days can be colored by negative self-critical thoughts such as, What’s wrong with me? My life is a mess. What will happen when they discover how useless I really am?

Such self-attacking thoughts are incredibly powerful, and once they gather momentum they are almost impossible to stop. One thought or feeling triggers the next, and then the next … Soon, the original thought—no matter how fleeting—has gathered up a raft of similar sadnesses, anxieties and fears and you’ve become enmeshed in your own sorrow.” (Mindfulness: An Eight-Week Plan for Finding Peace in a Frantic World)

I relate to this on so many levels. I don’t generally attack myself, but, in a millisecond, my mind provides me with ways of escaping when similarities in the present line up with similarities to the past. My mind will generate thoughts like, “Do you remember the last time you felt like this? Your ex caused you to feel like this. Your mother did this. Your father did this…” Ad infinitem. I will find a pattern and draw conclusions so quickly. I won’t even know that I’ve done it. Suddenly, I’m in tears or panicking or wondering if I’m safe. I will begin to wonder if anyone in my life is trustworthy. All because one thought was generated in my mind and I had to figure it out!

What can we do about it?

“You can’t stop the triggering of unhappy memories, self-critical thoughts and judgmental ways of thinking—but you can stop what happens next. You can stop the spiral from feeding off itself and triggering the next cycle of negative thoughts. You can stop the cascade of destructive emotions that can end up making you unhappy, anxious, stressed, irritable or exhausted.

Mindfulness meditation teaches you to recognize memories and damaging thoughts as they arise. It reminds you that they are memories. They are like propaganda, they are not real. They are not you. You can learn to observe negative thoughts as they arise, let them stay a while and then simply watch them evaporate before your eyes. And when this occurs, an extraordinary thing can happen: a profound sense of happiness and peace fills the void.” (Mindfulness: An Eight-Week Plan for Finding Peace in a Frantic World)

Ah yes, we are back at mindfulness again. It seems that there is so much more to it than coloring books.

For Getting Your Mindfulness On:

Mindfulness: An Eight-Week Plan for Finding Peace in a Frantic World

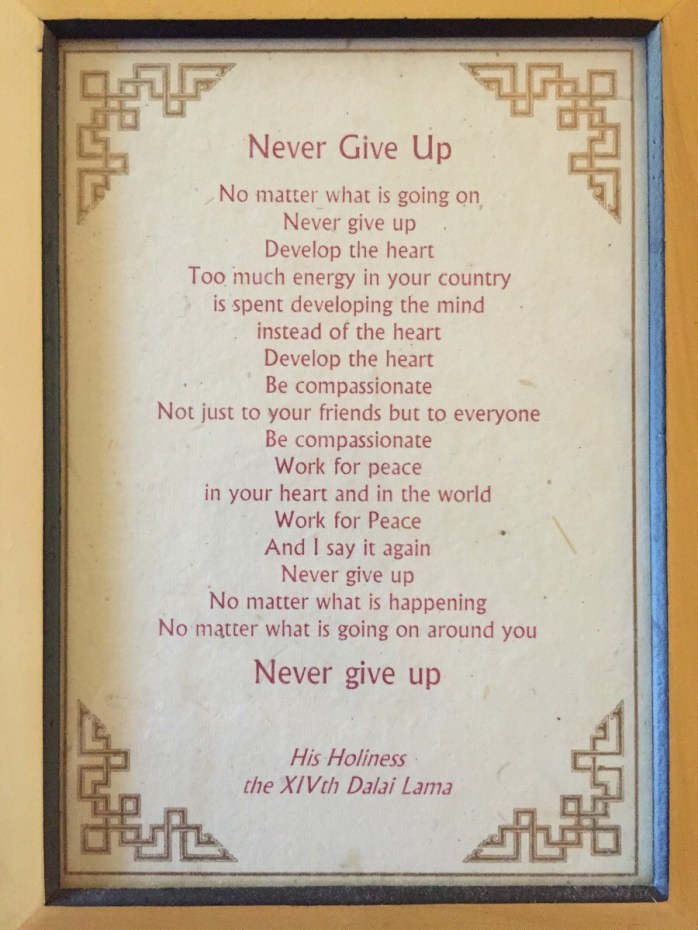

The Dalai Lama is Right

I saw this in a store today.

The Eight-Week Mindfulness Plan

I’ve written about mindfulness before. Everyone is talking about mindfulness. It is the cultural buzzword at the moment. All those coloring books abounding in bookstores and even garage sales? They’re taken from the ancient tradition of the meditation Mandala practiced by Buddhist monks:

It sounds like a pretty concept. Mindfulness. It’s even a pretty sounding word. Say it. Miiiiiiindfulness. Why is it emerging into Western culture with such force? Well, this is why:

According to Mark Williams and Danny Penman, “Numerous psychological studies have shown that regular meditators are happier and more contented than average. These are not just important results in themselves but have huge medical significance, as such positive emotions are linked to a longer and healthier life.” (Mindfulness: An Eight-Week Plan for Finding Peace in a Frantic World)

Williams and Penman state with evidence:

- “Anxiety, depression and irritability all decrease with regular sessions of meditation. Memory also improves, reaction times become faster and mental and physical stamina increase.

- Regular meditators enjoy better and more fulfilling relationships.

Studies worldwide have found that meditation reduces the key indicators of chronic stress, including hypertension. - Meditation has also been found to be effective in reducing the impact of serious conditions, such as chronic pain and cancer, and can even help to relieve drug and alcohol dependence.

- Studies have now shown that meditation bolsters the immune system and thus helps to fight off colds, flu and other diseases.” (Mindfulness: An Eight-Week Plan for Finding Peace in a Frantic World)

Here is what mindfulness meditation is not:

- Meditation is not a religion. Mindfulness is simply a method of mental training. Many people who practice meditation are themselves religious, but then again, many atheists and agnostics are avid meditators too.

- You don’t have to sit cross-legged on the floor (like the pictures you may have seen in magazines or on TV), but you can if you want to. Most people who come to our classes sit on chairs to meditate, but you can also practice bringing mindful awareness to whatever you are doing on planes, trains, or while walking to work. You can meditate more or less anywhere.

- Mindfulness practice does not take a lot of time, although some patience and persistence are required. Many people soon find that meditation liberates them from the pressures of time, so they have more of it to spend on other things.

- Meditation is not complicated. Nor is it about “success” or “failure.” Even when meditation feels difficult, you’ll have learned something valuable about the workings of the mind and thus will have benefited psychologically

- It will not deaden your mind or prevent you from striving toward important career or lifestyle goals; nor will it trick you into falsely adopting a Pollyanna attitude to life. Meditation is not about accepting the unacceptable. It is about seeing the world with greater clarity so that you can take wiser and more considered action to change those things that need to be changed. Meditation helps cultivate a deep and compassionate awareness that allows you to assess your goals and find the optimum path towards realizing your deepest values.” ( Mindfulness: An Eight-Week Plan for Finding Peace in a Frantic World)

Now that we’ve established that, what is it then that we are all about? Well, honestly, I’d like to be happy. This is what I am building. A happy life. Sure, we can wax philosophical until the end of the age about the true nature of happiness. Is it external to us? Is it an internal state? Is it a mere evanescent phenomenon and, therefore, a wasteful pursuit that we should abandon altogether in place of contentment? For the sake of the current discussion, I am leaving that discussion aside because it distracts us from what I really want to discuss. Mindfulness. And how we sabotage our own attempts to progress in life. How exactly do we sabotage ourselves? What are we doing wrong when we are trying so hard?

Williams and Penn explain:

“Our moods naturally wax and wane. It’s the way we’re meant to be. But certain patterns of thinking can turn a short-term dip in vitality or emotional well-being into longer periods of anxiety, stress, unhappiness and exhaustion. A brief moment of sadness, anger or anxiety can end up tipping you into a “bad mood” that colors a whole day or far, far longer. Recent scientific discoveries have shown how these normal emotional fluxes can lead to long-term unhappiness, acute anxiety and even depression. But, more importantly, these discoveries have also revealed the path to becoming a happier and more “centered” person, by showing that:

- when you start to feel a little sad, anxious or irritable, it’s not the mood that does the damage but how you react to it.

- the effort of trying to free yourself from a bad mood or bout of unhappiness—of working out why you’re unhappy and what you can do about it—often makes things worse. It’s like being trapped in quicksand—the more you struggle to be free, the deeper you sink.

As soon as we understand how the mind works, it becomes obvious why we all suffer from bouts of unhappiness, stress and irritability from time to time. When you begin to feel a little unhappy, it’s natural to try and think your way out of the problem of being unhappy. You try to establish what is making you unhappy and then find a solution. In the process, you can easily dredge up past regrets and conjure up future worries. This further lowers your mood. It doesn’t take long before you start to feel bad for failing to discover a way of cheering yourself up. The “inner critic,” which lives inside us all, begins to whisper that it’s your fault, that you should try harder, whatever the cost. You soon start to feel separated from the deepest and wisest parts of yourself. You get lost in a seemingly endless cycle of recrimination and self-judgment; finding yourself at fault for not meeting your ideals, for not being the person you wish you could be.” (Mindfulness: An Eight-Week Plan for Finding Peace in a Frantic World)

Does this sound familiar to you? I see myself in this. So, what will a mindfulness meditation program actually do then?

“Mindfulness…encourages you to break some of the unconscious habits of thinking and behaving that stop you from living life to the full. Many judgmental and self-critical thoughts arise out of habitual ways of thinking and acting. By breaking with some of your daily routines, you’ll progressively dissolve some of these negative thinking patterns and become more mindful and aware. You may be astonished by how much more happiness and joy are attainable with even tiny changes to the way you live your life.

Habit breaking is straightforward. It’s as simple as not sitting in the same chair at meetings, switching off the television for a while or taking a different route to work. You may also be asked to plant some seeds and watch them grow, or perhaps look after a friend’s pet for a few days or go and watch a film at your local cinema. Such simple things—acting together with a short meditation each day—really can make your life more joyous and fulfilled.” (Mindfulness: An Eight-Week Plan for Finding Peace in a Frantic World)

It is with the spirit of moving forward and truly building something better that I recommend Williams and Penman’s 8-week mindfulness plan. Get this book. Get the audiobook. Do the exercises. Their book is full of scientific evidence that will knock your socks off. You will get to know yourself and your brain better. You will understand why you do what you do and experience self-acceptance along the way rather than self-judgment. It will come as a huge relief rather than another reason to feel inadequate. It is in no way hard, and it will introduce you to a better way of thinking, doing, and being. I will be writing posts as I follow the plan for the next eight weeks, but wouldn’t it be fun to do it together? Send me your stories! I’ll post them!

Imposter Syndrome in Trauma Survivors

Here’s a story. I’m sharing it because it might elucidate something for you. I’ll open with a question.

Have you ever felt something like a fear of discovery? Like if people found out who you really were, then they would abandon you because, deep down, you’re really just a fraud? As if you are not legitimate in some way? You might even be broken or incapable. You don’t really have a right to be here.

It’s called Imposter Syndrome. Here’s a quick and dirty definition: “a concept describing high-achieving individuals who are marked by an inability to internalize their accomplishments and a persistent fear of being exposed as a “fraud”.” (Wikipedia)

Does this ring true for you?

This internal experience used to rule my life. I didn’t even know that it was a “thing”, but it is. The American Psychological Association discusses it, and the New York Times published an article elaborating on it (Learning to Deal with Imposter Syndrome). It’s a very real phenomenon. For people with profound trauma in their backgrounds, it’s even more relevant.

Why?

Here is my experience…

A while ago, when my oldest daughter was quite wee, I was getting to know a woman with a son close in age to my daughter. She was asking me the typical “Let’s Get to Know Each Other” questions. I was young and naive, and I had no problem engaging in social niceties. I did not realize that people rarely wanted truthful answers. So, when she asked me about my familial background and I answered truthfully, I was unprepared for her response which went something like this:

“I do not want to hear terrible stories about your life. I can’t tolerate things like that. Please don’t share such things with me.”

I was gobsmacked. I had only said that I had a difficult relationship with my mother. She had a history of depression and multiple suicide attempts. I didn’t describe in detail how she did it. I wasn’t reliving trauma in front of her. Honestly, I didn’t know what to make of such a reaction, but I felt a very particular sting. I couldn’t name it, but I respected her boundaries all the same. Whenever I saw her after that I simply smiled and said, “I’m fine. How are you?” That was what made her feel happy. I felt like a phony, but I get it. I grew up within the trappings of the nouveau riche country club crowd. Authenticity isn’t exactly a welcome guest.

A few years later, I met and became friends with another woman who, as our friendship deepened, pressed me for more intimate details about my past and present life. I was wary. I had never quite felt like my past life circumstances were my fault before, and I was beginning to feel under the microscope–judged. It wasn’t my fault that my mother was mentally ill. It wasn’t my fault that my father was a sociopath. Admittedly, I came from unusual circumstances, but I didn’t see myself as taking the blame for their bad behavior. Their problems did not originate in me. All the same, when I began to share some information, this woman responded in much the same way as the aforementioned woman. Remarkably, she, too, could not bear to hear that children were abused and mothers attempted suicide. She didn’t want to hear that fathers could be bad, and young women could be trafficked.

“I don’t like this story. I don’t want to hear it. It’s so negative. Tell a different story.”

Well, shit, I don’t like it either, but she asked. I was attempting to be authentic while, at the same time, not go “too deep” as it were. How does one form meaningful relationships with people when the past is so full of terrible stories? And why was I starting to feel so, for lack of a better word, broken? So rejected? As if I were the one who had done something wrong? I started to feel like I had to redact my own history in order to be socially and interpersonally acceptable. So, I did just that, and I was not quick to reveal myself to anyone. I adopted a persona, and it worked because I was raised to “try harder” in order to earn acceptance anyway. Not approval. Approval was The Dream. Acceptance, on the other hand, felt attainable. If your efforts passed muster, then you were found to be acceptable. Tolerable. Adequate. Lacking in interest, and that was a very good thing because if you weren’t of interest, then you weren’t open to criticism and a potential target for abuse or terroristic threats. These new experiences with social rejection felt eerily similar. Suddenly, approval was off the table as was a chance at intimacy and connection. Social acceptance and invitation became the options. Not inclusion.

I was learning quickly that many people were not interested in anything profound and meaningful particularly if it challenged their worldview, and suffering challenges paradigms. This is why so many people grapple with theodicy.

Years later, in a small group, I revealed truth about my past. Again. With disastrous consequences. My greatest fear at that time was that if I told the truth about past trauma I would be seen as inherently tainted–illegitimate–and, henceforth, at fault. I feared social alienation and rejection. That is essentially what happened. It was a devastating betrayal, but it was the greatest catalyst to healing I’ve ever experienced. Good ultimately came from that circumstance.

Sometimes wisps of this dynamic appear even now in statements like this: “Tell me something about your childhood, but don’t tell me something about your father. I don’t want to hear about how he killed an animal in front of you or something awful like that.” Yes, this is a boundary. I don’t want to violate anyone. People do have a right to determine what they do and don’t want to hear. For example, someone could say this: “Tell me a story about human connection that you’ve experienced, but don’t talk about sexual connection. I don’t want to hear about past sexual encounters.” That’s a boundary.

What is the difference between the two boundaries?

My sexual encounters were by choice but trauma is not. Generally, unless there is a kink at play, people don’t require a witness to the sexual narrative in order to experience validation, acceptance, and approval in the context of relationships. In the context of developing relationships, however, people do, at some point, need a witness during the process of narrative exposure in order to feel minimally acceptable, and optimally approved of, particularly if there is trauma within their narrative. Being told that their narrative is not tolerable is, in part, stigmatizing because it casts a pall on the personal experiences of people causing them to experience less authenticity within their relationships and even within their self-perception. Necessary deletions of one’s personal narrative made in order to survive socially in different contexts affects the healing process. We cannot integrate properly after trauma if we can’t even talk about what happened to us because other people find our stories unpalatable.

Yes, the stories are bad. That’s why trauma survivors suffer so terribly. Part of being compassionate people is listening and acting as witnesses to those who are suffering in silence and solitude fearing that no one will ever hear their entire truth and still want and love them after disclosure. This is one of the unbearable curses of living with trauma.

This is why the variation of Imposter Syndrome in survivors of trauma needs to be addressed. The ontological loneliness is real. The fear of being discovered is real, and it’s legitimate. The way out is telling our stories. All of them. To very safe people who will sit with you while you lay them out. They won’t judge you. They won’t blame you. They will act as witnesses to everything you have heard, seen, and experienced.

And, they will accept you as you are today. They will approve of you no matter what you did in the past. And, why would anyone do that, you ask?

Because your past self got you to where you are today, and that’s something to be very proud of. Regardless of your past experiences, you’ve made it this far. That’s a story worth telling. Shamelessly.

Deep Programming and Core Beliefs

I have discussed core beliefs on this blog (Core Beliefs and Double Distortions, Gridlock and Core Beliefs, Core Beliefs) . After my “career” in therapy, I thought I’d covered all the ground until I landed on core beliefs. I learned that after putting in the time and energy along with all the blood, sweat, and tears I could be cognitively intact, mindful, self-actualized, burgeoning with insight and self-regulation and still influenced by these almost subconsciously held “core beliefs”. EMDR, in part, addresses these core beliefs so that we can change them and adaptively process trauma in order to heal and ultimately move on free of negative, internal influences.

That’s a mouthful. What does this look like in terms of recovery because it sounds relatively easy on paper? I’ll use my journey and process as an example to further elucidate the premise.

My father was a member of a certain military branch’s elite special forces unit. It was just yesterday that one of my daughters commented on him and his participation in military operations as a member of this unique special forces squad. She had been reading a book in one of her university classes wherein this unit was described by another member of the military–a soldier who had direct contact with my father’s unit. In an interview, he described them as barely human. They kept to themselves and exhibited no emotion. They were so intimidating that other soldiers instinctively avoided them. They exuded danger. They were feared. They were the assassin’s assassins. They were the group that trained other soldiers on torture. They made sure that everyone knew just how expendable they were ensuring that the most questionable orders were followed. They were the men hired to be mercenaries after discharge from military service. No one fucked with these guys. Ever.

I told my daughter that this book’s description described my father perfectly. It was validating to hear it particularly in the context of a book about war from the perspective of other soldiers. It explained him somehow. His actions and treatment of me had little to do with me. Cognitively, I have finally learned and internalized that. He was acting in accordance with his nature, and yet I was still left with old programming. I had to get rid of it even though I wasn’t entirely sure what I had to get rid of. Something lurked in my subconscious. A dark and misty fear. Untenable.

Whether or not it was intentional on his part, my father did participate in programming and torture techniques that were used in the military when I spent time with him. Was he re-living his military days as a civilian? Was I viewed as the enemy? Is this why he did the things to me that he did? Perhaps he couldn’t help himself. Maybe he liked it. He was a sadist. It doesn’t matter. When you’re stuck with “programming”, which is what core beliefs are, it’s vital to search it out and delete it.

How do you do that? How do you even go about finding it?

All of my old and deleterious programming/core beliefs emerged while I was trying to fight against abuse in my marriage and during the first year after my ex moved out–during the initial trauma processing. I do not recommend engaging in this process alone. It is excruciating in every way, and my therapist warned me that it would come for me. My circumstances might be viewed as unusual. I am not the only person raised by a borderline mother. I have written extensively about her and what healing from that kind of childhood looks like. It’s painful and difficult, but it can be done. My father, on the other hand, was a highly training killing machine to put it bluntly. His humanity did not survive his time in the military nor did it survive his own childhood. His father, my grandfather, was also a member of a specialized military unit with ties to certain alphabet agencies in the government. He grew up under inordinate emotional and physical deprivation, and he continued that tradition with me. It is what he knew. It was our family’s tradition.

As is the case with family traditions, belief statements go along with them. For some families, those statements of belief might be, “We always vote Democrat,” or “We are a Christian family with traditional values.” Sometimes it’s whimsical–“We love Christmas!” or “We always eat Swedish meatballs on Easter!” Sometimes it’s dangerous–“We hate Jews,” or “We don’t go downtown at night because those people are everywhere and might hurt us.” Every family has their belief system much like a statement of faith in a church. Sometimes it is implicitly stated. Other times it’s not, but everyone understands what is believed based upon attitudes and actions. Family culture is often the first place to look when attempting to root out core beliefs and/or programming.

The foundational core belief that almost all of the other ones in my father’s home were founded upon was this: “You are expendable.” It is entirely appropriate considering who my father was. It would only emerge in me when I was attempting to assert myself under extreme pressure, and it was always followed by profound feelings of extraordinary despair as if life were meaningless. Death seemed like a welcome option. I found myself thinking, “Why bother?” Why bother trying to do anything? If I am expendable, then my hopes and efforts to affect change in my life were utterly futile. To quote the Borg from Star Trek, resistance is futile. Why not just fall into the warm ease of the collective and give up my distinctness? Why not just be assimilated into whatever I am attempting to fight and give up? And yet I never could.

This type of thinking goes against everything that I believe as a person which is often your first clue that you are dealing with a core belief or trauma-induced programming. When you find yourself behaving and making choices that go against your own set of consciously held beliefs, then you might be dealing with core beliefs/deep programming.

Those “thoughts” are “programming” at its finest. How are these core beliefs/programming fortified and glued in place? Through trauma. And, sometimes the trauma is extreme, but it doesn’t have to be in order for it to be effective. For example, a child may witness a parent physically abuse the other parent. It is traumatic for children to witness abuse in their families, but imagine that there were words spoken as well. In addition to the physical abuse, perhaps one parent saw the child crying at seeing the abuse. Suddenly, the abusive parent shouts at the child while raising a fist, “You better stop crying, or I’ll give you something to cry about!”

What belief might have been planted here in this moment? There may have been many fears and insecurities related to safety and an emerging belief that one parent is an all-power perpetrator. What about something else like, “If I show weakness or emotion, then I’ll be hurt,” or “If I attempt to stand up for myself, then I’ll be threatened and possibly hurt.” There are other possibilities in terms of parentification or even failed parentifcation. Helplessness. Powerlessness. Ontological fear. Fear of death.

The now fallen Bill Cosby once joked in a stand-up routine that his father told him when he was a child that he could take him out of this world just as easily as he brought him into the world. What’s more, he could make another one who looked just like him. So, as if his father were the great Santa Claus in the sky, he better watch out. He better not cry. He was watching lest he be “taken out”. His late 1970s delivery of this joke was humorous in its extremity, but it was funny because it was true in the sense that children actually believe their parents when they say things like this. Parents are as God to their children for a long time. What we see and hear from them as young children roots itself in our subconsciousness and influences us for years. It does not matter if it’s the embodiment of deception. It doesn’t matter if we cognitively and consciously disagree with it. If your emotions believe it to be true, then you will be a house divided prone to self-sabotage and fumbling your way through myriad missed opportunities. This is the power of deep programming aka core beliefs.

So, what did I do with that deep core belief that told me at key moments in my life that I was expendable? Eventually, I had to sit with it. It rose to the surface numerous times at the tail end of my marriage. After the last sexual assault, I truly felt expendable. Worth nothing. When my doctor told me that I needed pelvic floor corrective surgery due to years of sexual violence, I felt…broken in a distinct way. It was so profoundly personal. I sat with that belief. I sat with all the emotions that came with it, and, truthfully, I wanted to die. Throughout most of 2016 I wanted to die. I looked back over the landscape of my life, and I felt inordinate anguish. How did I get to this point? What the hell happened?

But then my therapist said something to me. He asked me why I fought so hard to get out of captivity after I was abducted. He asked me why I fought so hard to get out of my marriage once I realized it was not good for me. Why did I leave both my parents behind? Why did I make those decisions? I didn’t want to answer. I felt too vulnerable to speak about any of it. Frankly, I was tired of discussing my weird life. I have lived a weird life, and I grow tired of it sometimes.

After much prodding, I finally answered, “I fought and continue to fight because…I’m just not going out like that. I won’t let these bad people get the best of me. I just…won’t.”

“So then…you don’t honestly believe any of it then, do you? You wouldn’t fight so hard if you truly believed that you were expendable. You fight so hard to prove that you are, in fact, the very opposite. The anguish you feel then is because the people who were supposed to love and support you have never seen you for who you are. For the girl and woman you see yourself to be, and that is the heart of your pain. You know the truth, and they only know the lies. You feel such pain because you don’t know what it’s like to be truly seen, and the invisibility is too much sometimes.”

And there it was. My father’s core belief that I was expendable because he was expendable never truly settled into me. I fought so hard to prove him wrong because I wanted what everyone wants from a father. If I couldn’t get love from him, then I, at the very least, wanted acceptance. Please, just see me! I couldn’t even get that. I would always be disposable, and, in a way, that was true for my mother as well. If I did not meet her needs and make her happy, then I was worth little to nothing. This was reinforced in my marriage repeatedly. Being ignored for almost three years tapped into that latent belief that I was expendable and resurrected it. I felt like the walking dead. A ghost. Present but never seen.

This is why it is imperative that you stop running from what pains you and learn to tolerate your own personal distress. It is within your inner turmoil that your answers lie because that which you fight in terms of your own inner demons may be the very thing that is saving you. We may feel a certain thing to such a degree that it pushes us beyond our perceived limits, but our inner fight is there, too, attempting to prove to us that what we feel isn’t true at all. We are, in fact, worth something. We are, in fact, worth knowing, loving, accepting, and fighting for. The anger we feel that is often internalized and experienced as depression and desolation screams this out at us.

If this resonates with you at all, then I encourage you to do the hard thing and explore the darkness. Don’t do it alone. Have someone on stand-by at all times who will, at a minimum, check in with you. But, dare to go into your own dark corners and unopened boxes. Therein may lie your redemption.

Fight for the life you want and deserve. Never stop.

The Ego and You

Relationships can be very rewarding, but, truthfully, they can be difficult. This is true for everyone regardless of any residual issues you might face in terms of family of origin, trauma, and relationship history. This makes personal development in terms of interpersonal effectiveness, perspective-taking, validation, and empathy development all the more important. Why? Well, a proper development of empathy and perspective-taking enable us to dismantle a lopsided ego when it may, under pressure, take its edification from the disempowerment of others in order to empower itself, and that pursuit and process can be extraordinarily subtle. The question I often ask of myself is this:

Is your ego driving you, or are you driving your ego?

In order to continue to develop a more integrated identity (eg0) and increase interpersonal effectiveness and emotional maturity, it is vital to develop insight into our own behaviors and drives and the behavior of others (empathy):

As James Mark Baldwin aptly stated, “Ego and alter are born together”. What he meant by that is our sense of self emerges in close relationship to our sense of others (and how they treat us). Indeed, because our “selves” exist within interdependent networks of other people, because we initially understand ourselves through the lens of mirrored others, and because our identity is very much about narrating and legitimizing our actions to others, a key aspect of ego functioning is the capacity to understand others in a complex manner. Whereas insight refers to the capacity to understand one’s self, empathy refers to the capacity to understand others. So central is this ability that a recent, modern psychodynamic treatment is called mentalizing, which teaches individuals steps for developing more complex, richer, less judgmental and reactive narratives for describing and explaining the actions of others. (The Elements of Ego Functioning)

Note this idea: “we initially understand ourselves through the lens of mirrored others….” This concept explains, in part, why family of origin trauma is so significant in personal development. If we initially understand ourselves through the perceptions of others, then our budding identities could often be founded upon distortions and extremities when we hail from abuse. Furthermore, this would be normalized because this is our starting point in life and often the cornerstone for our core beliefs.

In my experience, remaining at this developmental stage is often the cause for interpersonal difficulties and suffering. When we continually remain in a state wherein we understand ourselves through the reflective lens of other people we fail to develop insight or even a more developed empathic response towards others because we are functioning from a deficit. What do I mean by that? When you are continually looking to understand yourself through the experiences of other people, your reference point for all your experiences becomes, oddly, self-referential even though you are looking externally for your legitimacy and validation. The mechanism underlying this is the need to consistently legitimize and identify yourself rather than already feeling existentially or ontologically legitimate, and that need is internally driven. It is the ego driving you. The extreme version of this is narcissism. In that context, a person is looking to others for “narcissistic supply” which is:

“a psychological concept which describes a type of admiration, interpersonal support, or sustenance drawn by an individual from his or her environment. The term is typically used in a negative sense, describing a pathological or excessive need for attention or admiration that does not take into account the feelings, opinions or preferences of other people.” (Wikipedia definition)

Essentially, you are building an identity with borrowed or even stolen bricks and repairing a wounded ego by the same means. You are not building, maintaining, or developing a sense of self through an internal process of growth. While it is absolutely necessary to experience support, love, and validation from other people in order to experience a rich and meaningful life, it is important to note the difference here.

We have to ask important questions like: Who is responsible for meeting my needs? Who is responsible for making me happy? Who is responsible for my well-being and sense of personal significance? How do I build a meaningful life and experience rewarding relationships that enrich me and the other person while promoting growth? How do I continue to grow personally even in the midst of a social and emotional drought? How do I feel good about myself when there is no one around to make me feel good about myself? How do I learn to validate and motivate myself?

Why does this matter? Well, on a truly fundamental level, what might happen when you are faced with criticism? It becomes an attack on identity instead of an opportunity to generate growth and listen to another person’s legitimate perspective which may strongly differ from yours. Why might that be the response? If my sense of self is perceived and developed through other people’s experiences of me rather than a solid understanding of myself, then criticism would be, of course, devastating.

What if you are confronted with a hard truth about how you relate to other people? What if you hurt someone’s feelings? What if you have bad relational habits of which you are not aware? Or, what if your sense of self is still largely founded upon what your family believes about you or even an abusive ex-partner? What if deeply rooted core beliefs are dictating the functioning of our egos? What if your sense of self is founded upon social convention, wealth, or meeting expectations and, suddenly, you lose your standing? All this is to say that it is imperative that we devote time and effort to developing insight into ourselves so that we become not only more empathetic but also more integrated in order to be more interpersonally effective.

What might ego-driven behavior look like in terms of personal relationships? We experience this often, and we certainly feel it. The sting of a wounded ego is very particularistic. I’ll give you a more extreme example to illustrate the point:

When my ex-husband and I would try to work out relational issues, it almost always failed. His self-assessment was largely based upon his professional life and success, therefore, my experience of him created an inescapable dissonance. Whenever I told him how I felt or even my experience of him he would say something like this:

“No one complains about me. I have asked other people if I’m like that. I’m not. That hurts my feelings that you even think that about me. I think that you are a broken person because of the things that have happened to you, and maybe you don’t perceive reality as it is. That’s what is happening here. Besides I don’t even remember what you’re talking about.”

This is an ego-driven response.

- “No one complains about me.” His sense of self and his behaviors are understood through others. Were they not, then he would not have used other people’s perceptions to minimize or dismiss mine. Furthermore, this response conflates his experiences with other people and our experience in relationship together. People can and do behave differently with others and within the contexts of different environments. It is not unusual at all to find out that a person, for example, has a bad habit, addiction, or even profound personal struggles “behind closed doors”. To the shock and dismay of their friends and colleagues, everyone says, “I would have never guessed. S/he never gave any indication that they struggled in that way.”

- The presence of blame. Blaming is a way to externalize discomfort, distress, and anger. As Brene Brown puts it, “Blame is the discharging of discomfort and pain. It has an inverse relationship with accountability.” Once the blame sets in, shame follows quickly. To quote Brown again, “Shame, blame, disrespect, betrayal, and the withholding of affection damage the roots from which love grows. Love can only survive these injuries if they are acknowledged and healed…Shame corrodes the very part of us that believes we are capable of change.”

- The absence of empathy and validation. “That’s what is happening here.” Speaking in terms of omniscience, as if he is the expert on my experiences and heart, shows a lack of empathy, personal insight, and compassion. There is no interest to learn and grow. There is, however, a strong desire to be right as well as another desire to deny.

- The presence of gaslighting. This is an example of perceptual manipulation which defines gaslighting, and it characterizes ego-driven responses. Basically, one must manipulate, suppress, and force change upon the perception of the other person in order to mold it to one’s own perceptions since one’s self-perception is dependent upon others. It is vital for underdeveloped or dis-integrated ego survival that external supply is consistent because dissonance, which spurs growth, is not allowed. Growth is often very painful, and survival and pain often don’t make friends easily.

When you experience something like this in life, and you will, understand that this can be the mechanism behind behaviors like this. Does it hurt to be a part of this kind of dance? Yep. It is much easier to process, however, when you understand the process, and it’s also a wonderful reminder to tend to your own ego and growth process. It’s how we heal, grow, and become people worth knowing. We become better people, and that’s a journey worth taking.

For an outstanding article on ego functioning, read this:

A Sunday Thought

“Sometimes where you are is not where you belong. It’s just what you’re used to.”

A Sunday Thought

“If I quit now, then I will soon be back to where I started. And when I started I was desperately hoping to be where I am now.” Unknown

The Buffer and Rat Park

I went to therapy on Tuesday with a migraine.

I have to pause for a moment and talk about migraines, pain, and trauma. Whenever I have mentioned the nightmare known as The Migraine on any blog, well-meaning people have offered helpful comments. I certainly want more good information particularly if I don’t have it, but it must be explained first that a migraine is not a headache (please bear with me as I will make a point). It’s a neurological event that, if left untreated, can leave lesions on the brain, thusly, leaving the brain vulnerable to a future ischemic attack. Who knew? I certainly didn’t. You can’t fool around if you have “chronic migraine” (15 or more attacks in a month). I am one of those people. A dark room, a few Excedrin for Migraine, and lavender oil don’t help me. Regretfully…

I began experiencing migraines after an auto collision, and these pain-mongering menaces arrived days later and never left.

They are the bane of my existence. I have tried everything known to, well, anyone for 13 years now and continue to pursue every avenue of treatment and prevention available from PT, diet therapy, pharmaceutical interventions to yoga, breathwork, chiropractic, aromatherapy, massage, acupuncture, myofascial release work, European herbal remedies…you name it. They don’t stop. Ever. They might abate for a while, but they always return. I was in the ER on Tuesday night for an infusion of the magic cocktail due to a migraine that lasted around 16 days. It sucked, and I felt very discouraged.

Once again, I was in therapy during this round in the ring with Mega Migraine, and my therapist, who has experience counseling people with chronic pain, tried to coach me through the pain suggesting different strategies. He also asked me carefully if past trauma played a role in the frequency of my migraines–a legitimate but admittedly tiresome question. At times, however, one starts to feel patronized. I did my best to answer his questions while I massaged stabbed myself as if I had an ice pick trigger points and squinted at him possibly slurring my words.

This is where, I observe, that people with PTSD or past trauma might experience a defensive response (looking catatonic can be defensive in nature, I suppose). I do, at times, feel emotionally defended when people suggest that migraines or any other illness are psychosomatic if you’ve experienced trauma; that is an oversimplification as humans are far too complex. I didn’t, however, defend myself at all on Tuesday because I was in too much pain, and, for what it’s worth, I know the emotional stressors that trigger a migraine attack. I also know that a car crash has damaged the nerves in my neck (neuropathic pain), and I also have vasculitis in my CNS thanks to SLE (Lupus) not to mention genetics. These are three “quantitative” etiologies for these migraines that have nothing to do with PTSD or past trauma; so, I felt safe enough to address the more qualitative reasons.

For example, the sound of my mother’s voice will trigger a migraine in a certain part of my head–around the trigeminal nerve to be exact–in about five minutes. This is a primary reason I’m pursing EMDR. That is a classic trauma-based somatic response. I want that outta here! If one of my daughters becomes labile and needs to go to the Behavioral Health ER for something like suicidal ideation or a sudden onset of a mixed state, I will most likely experience a migraine within 12 hours after that. That is a classic stress trigger for me. My ex-husband’s antics will trigger a stress-related migraine particularly if it hurts one of my daughters in a meaningful way, but this does not mean that a migraine emerges out of the ether and descends upon me, the migraineur, in some sort of psychosomatic fog. Blood pressure, adrenaline, and cortisol most likely play a huge role in affecting the blood vessels in the brain thanks to the stress experienced from these events, thusly, causing a migraine. We are not machines even though Descartes would like to attribute such a description to humans.

Westerners can be quick to banish anything stress-related and almost act as if the resultant symptoms are not real. Stress causes heart attacks. That’s as real as it gets.

Look at the rise of hypertension and diabetes or even cancer. One can point at diet first, but what fuels the poor diet choices (leaving out low income and class issues)? Stress. Why, for example, won’t people give up their favorite foods loaded with salt, sugar, and unhealthy fats? Stress. People are often trying to mitigate stress using the closest thing at hand to do that–food products i.e. substances. The Big Three make us feel better for a time, and that’s real and measurable. Reduce stress and one observes a subsequent reduction in illness and its damaging effects on the body and mind. This is a known principle. Once stress is reduced, the automatic habits that go along with that stress tend to reduce as well i.e. emotional and/or stress eating, increased alcohol intake, increased caffeine intake, increased substance use for stress and emotional management. It’s tough, however, if the very things used for stress mitigation are themselves addictive which, alcohol and opiates aside, dairy and gluten are as their proteins occupy the opiate receptors in the human brain. That’s why it is such a pain in the ass to give them up. What’s more, the very things that ultimately exacerbate our stress levels and level our health surround us namely industrialized food products. Our biology works against us here.

What if then one has done everything one can, but the stress cannot be reduced?

Isn’t that the magic question though? I can’t control my children or my ex-husband. You can’t make an infant sleep through the night nor can you control another person’s behaviors or driving habits, and it’s these very things that potentially exacerbate myriad illnesses in us if we are already under internal pressure–how other people’s choices affect our lives.

Enter The Buffer.

What is The Buffer?

Well, we are supposed to have natural buffers in our lives that help support us in ways that our proxy support systems– Fat, Sugar, Salt, Caffeine, Entertainment, Substances, and other things–do. The emotional soothing and regulation that we get from these sources are supposed to be provided to us from something else. Like what?

Let me introduce you to Rat Park. What is Rat Park?

“The Rat Park Experiment aimed to prove that psychology – a person’s mental, emotional, and psychosocial states – was the greatest cause of addiction, not the drug itself. Prior to Alexander’s experiment, addiction studies using lab rats did not alter the rat’s environment. Scientists placed rats in tiny, isolated cages and starved them for hours on end. The “Skinner Boxes” the rats lived in 24/7 allowed no room for movement and no interaction with other rats.

Using the Skinner Boxes, scientists hooked rats up to various drugs using intravenous needles implanted in their jugular veins. The rats could choose to inject themselves with the drug by pushing a lever in the cage. Scientists studied drug addiction this way, using heroin, amphetamine, morphine, and cocaine. Typically, the rats would press the lever often enough to consume large doses of the drugs. The studies thus concluded that the drugs were irresistibly addicting by their specific properties.

However, rats by nature are social, industrious creatures that thrive on contact and communication with other rats. Putting a rat in solitary confinement does the same thing as to a human, it drives them insane. If prisoners in solitary confinement had the option to take mind-numbing narcotics, they likely would. The Skinner Box studies also made it incredibly easy for rats to take the drugs, and it offered no alternatives. The need for a different type of study was clear, and Alexander and his colleagues stepped up to the plate.”

Are you curious yet?

“The goal of Bruce Alexander’s Experiment was to prove that drugs do not cause addiction, but that a person’s living condition does. He wanted to refute other studies that connected opiate addiction in laboratory rats to addictive properties within the drug itself. Alexander constructed Rat Park with wheels and balls for play, plenty of food and mating space, and 16-20 rats of both sexes mingling with one another. He tested a variety of theories using different experiments with Rat Park to show that the rat’s environment played the largest part in whether a rat became addicted to opiates or not.

In the experiment, the social rats had the choice to drink fluids from one of two dispensers. One had plain tap water, and the other had a morphine solution. The scientists ran a variety of experiments to test the rats’ willingness to consume the morphine solution compared to rats in solitary confinement. They found that:

- The caged rats ingested much larger doses of the morphine solution – about 19 times more than Rat Park rats in one of the experiments.

- The Rat Park rats consistently resisted the morphine water, preferring plain water.

- Even rats in cages that were fed nothing but morphine water for 57 days chose plain water when moved to Rat Park, voluntarily going through withdrawal.

- No matter what they tried, Alexander and his team produced nothing that resembled addiction in rats that were housed in Rat Park.

Based on the study, the team concluded that drugs themselves do not cause addictions. Rather, a person’s environment feeds an addiction. Feelings of isolation, loneliness, hopelessness, and lack of control based on unsatisfactory living conditions make a person dependent on substances. Under normal living conditions, people can resist drug and alcohol addiction…

Today, psychologists and substance abuse experts acknowledge the fact that drug and alcohol addiction involves transmitters within the brain. Certain chemicals latch on to different receptors in the brain, altering the way users think and feel. The user becomes addicted to the high he or she experiences while on the substance, and soon has to use it all the time to cope with other feelings. The more neuroscience discovers about addictions and the brain, the more physicians can find solutions to treat addictions.

What scientists today realize is that addiction is as mental as it is physical. Humans do not have to be physically isolated, like the rats in the Skinner Boxes, to become addicted to substances. Emotional isolation is enough to produce the same affects. Humans cope with their feelings of dislocation with drugs and alcohol, finding an “escape” or a way to smother the pain. A human’s cage may be invisible, but it is no less there.” (online source)

Many people have written about Rat Park. My takeaway is this: In order to heal and progress in a meaningful way we must build a buffer. We must emerge from our human cages with as much dedicated effort as possible and do something different than we’ve been doing.

Why do I call it a buffer? That’s what my neurologist called it, and it struck a chord. She had prescribed five medications for me to take in order to prevent constant migraine pain. Five. It’s ridiculous. When I asked her why so many she said, “These medications are your buffer. Your life is so stressful. You have nothing in your life properly supporting you right now. Until you have real buffers in place like people you can count on consistently to alleviate some of your intense stress like your sick kids and abusive husband, you need the medication. Otherwise, you won’t be functional because your brain is just too irritable. Your circumstances have to change, and the meds are bridging the gap for you until they do.” Well, that’s a lousy answer, but is that not a true answer for so many of us? Who is absorbing the stresses and inequities of our situations? Us. Our bodies. Our minds. Our spirits. We are caged in circumstances that we did not entirely choose.

Psychologist Adi Jaffe states:

“To make matters more complicated, we know that biological influences related to genetic differences, neonatal (birth-related) circumstances and early nutrition can alter brain mechanisms and make people more, or less, susceptible to the effects of trauma. For instance, we now know that early life trauma alters the function of the Hypothelamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, making individuals who have been exposed to trauma at an early age far more susceptible to stress, anxiety and substance use; or that hypoxia during delivery (certainly a form of trauma) can increase the chances of mental health defects later in life. Like the Rat Heaven experiment, it should be somewhat obvious that without these early traumas, the individuals in question (those who struggle with addiction) would experience less “need” for heavy-duty coping strategies like, let’s say, opiates. So biology is important here at least in this regard.

So trauma and stress are not at all objective truths but rather individually determined patterns of influence. I am fully on board with making sure that the treatment system we use does not exacerbate the problems that stress and trauma bring about (so no shaming, breaking-down, or expulsion of clients for their struggles), but I think that the picture this TED talk and the related book presents is far too simplified to be as helpful as we want it to be. I believe that more focus should be given to improved prevention efforts in order to reduce the likelihood of these early traumas and therefore of later drug seeking experience in the first place. I also know that significant efforts are already being put into this sort of work through a multitude of social-services organizations and government agencies. Needless to say, the demand for drug use has not abated despite these efforts. It’s been happening for at least 8000 years already and I’m thinking it’s here to stay.” (Adi Jaffe)

Where does this leave me? What is my point? It’s not as if we can suddenly jump from our circumstantial cages and swan dive into a metaphorical Rat Park as lovely as that would be, but can we migrate to such a place given the chance to make small, meaningful changes consistently? Is that possible? I think so.

How?

Well, that’s what I’ve been trying to do for the past 13 years. The reason that I know it’s been 13 years is that the very auto accident that resulted in my now ever-present migraines occurred two weeks after I ended my relationship with my father–my primary abuser. That was a monumental choice in my life, and, while I did not know it at the time, it set me on a course of recovery. The trajectory of my life changed in that moment. A few years later, I ended my relationship with my mother, my secondary abuser. And, a year and half ago, I ended my marriage. I finally climbed out of that cage. No more abuse. From anyone.

Was it hard? Excruciating. It is hard for me to describe the emotional suffering and turmoil I experienced last year. The pain and grief were nothing if not backbreaking. I think I wept more last year than I have in my entire life, and it wasn’t because I missed my ex-husband. It was simply an overflow of pain, grief, loneliness, fear, and existential alienation that I was forced to set aside in order to survive. I had pretended to be fine for so long that when it came time to be truthful with myself, it became a reckoning. I spent many sleepless nights sobbing. I can barely write about it even now. I felt like I was somehow vomiting forth my viscera through my tears, but, I think, it all had to go. Years and years of absorbing the inequities, the emotional and physical abuse, and believing that in order for others to be happy I had to diminish had to be sucked from me as a poison. And do you know what has happened? Unbelievably, my Lupus blood panel is now normal. For the first time since my diagnosis, I am in remission.

My neurologist also wants to look at reducing those medications. I am getting better.

I enrolled in grad school.

And…ahem…I met someone, y’all.

Yes. This is hard. I have never lied on this blog about the inordinate difficulty involved in turning your life around. BUT…it is possible. And that is what I have always wanted to know. I never cared if creating a life worth living was hard. I only wanted to know if it was a possibility for me.

Is it possible? Yes, it is.

So, excuse my language, but fuck hard. Do what is possible because, while it might seem impossible, it’s not.

You can do this. Keep going.