Out of the Mire

…because thriving is the goal

You are the Masterpiece

I recently spoke with a beloved friend experiencing emotional pain due to a family interaction. Her sentiments were familiar. This interaction was similar to an older one, and it brought forth latent feelings of ontological insignificance.

“I don’t matter.”

Isn’t this something we can all understand? People treat us badly. They brush us aside. They lash out, ignore us, make us the problem, blame us, gaslight us, talk about us behind our backs, and the like, and we get hurt. Sometimes profoundly. And, we’re left wondering why. Don’t they know that we matter, too? Don’t we? We matter, right? Right? Right…?

I thought about it. Is it possible to explain that we are indeed significant and valuable even in the context of mistreatment, neglect, and abuse? What might drive that point home?

This might…

This painting sat in a Norwegian industrialist’s attic for six decades after he was told by the French Ambassador to Sweden that it was a fake. Boom. There it is. It was not authenticated. It was indeed a genuine work of Van Gogh’s, but Mr. French Ambassador, mistaken, gave the wrong information to Mr. Mustad, the Norwegian industrialist, causing him to feel great shame for buying a fake, thus, motivating him to hide the allegedly forged painting in his attic for over sixty years. It’s all very dramatic.

What an incredible story! Can you imagine being the one to stumble across a missing Van Gogh in your relative’s attic? That would be the find of the century, and, in this case, it was. The art world went crazy. The angels sang. Curators wept. The story of the return of the missing Van Gogh ran in newspapers all over the world. And, the questions on everyone’s minds were, “What kind of derp declares an authentic Van Gogh a fake? Who hides a genuine Van Gogh in their attic for over half a century?” The French Ambassador to Sweden and a Norwegian industrialist apparently.

The obvious point here is that everyone can grasp that even though the painting was neglected, ignored, and even misjudged, its value and significance were always intact even if it wasn’t immediately recognized. This painting mattered even though it remained in an attic for sixty years. No one said, “Maybe the painting isn’t really valuable. I mean, it was stored in an attic. Only worthless things are stored in attics.” Upon hearing this story, the general population understood that the problem was with the people who did not recognize what they had–not with the painting itself. Once the painting was free of the family who owned it and in the hands of well-trained curators, its origins were recognized, and it took its rightful place in the catalog of Vincent Van Gogh’s works.

How does this apply to us? Well, so often when we are mistreated we assume, as do others, that the problem lies with us when the problem really lies with the people mistreating us. We believe that a person would only neglect or mistreat us if we lacked value or mattered little when the truth is that people mistreat others because they have a broken moral compass.

Our value is never to be questioned. NEVER. Just because a person doesn’t recognize our worth, our potential, or our significance doesn’t mean that we lack it. It simply means that the person with whom we are interacting may have issues of their own, and we may need to seek out more supportive people who see us more clearly. Like the curators who recognized the Van Gogh for what it was, we need to surround ourselves with people who see us for who we are. Many paintings come to museums in need of restoration. Their value is highly significant to the art world, but they are not ready for display. There are people highly trained in restoration, and those people painstakingly restore these works of art so that one day these historically significant pieces will be put on display for the world to see. We are really no different. All of us are significant and in need of restoration. Just like these paintings, the degree to which we need to be restored does not detract from our value or significance.

Part of that restoration process is getting rid of the French Ambassadors who would declare you a worthless fake and the Norwegian industrialists who would be embarrassed by you and neglect and hide you away. These are unsafe people who hinder and deceive us.

As part of your restoration process, ponder the idea of being priceless. How might you think differently and, thus, treat yourself and others if you truly believed that you were significant and truly valuable? That this was never up for grabs. And, because this is fun, if you were a work of art, what would you be? Would you be a work of impressionism, pointillism, fauvism, cubism, classicism, mannerism, the baroque? Would you be a Rodin or even an architectural piece by someone like Brunelleschi or Michelangelo? How would you express yourself and worth in art form? This is important because works of art are often viewed as priceless even when they’re badly damaged, and, if we can view ourselves objectively as priceless, then we can begin to internalize this truth. Once we see ourselves as such, it’s easier to see where we have believed the lie that we don’t matter and are worthy of mistreatment. If a piece of art deserves careful treatment and respect, then how much more does a person?

“Art enables us to find ourselves and lose ourselves at the same time.” Thomas Merton

Resources:

Long-lost Van Gogh painting found in attic

The Collection of Art at The Hermitage–a virtual tour of the collection on display at the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. I had the privilege of visiting this museum. It is well worth visiting even if it’s just virtually.

Cleaning Up Messes

My youngest daughter asked me an unusual question today. She asked, “Mom, how come you turned out so normal?” We were in the car, and her question came out of the blue. She knows little about my history. It’s not as if I sit around the house talking about the good ol’ days when I was in captivity. How inappropriate would that be? I asked her why she asked me that question. She replied, “Well, your mom and dad weren’t nice to you, were they? How come you know how to be nice to us? How come you’re a good mom when you didn’t have one?”

I was stunned. That’s a very perceptive question coming from a 10 year-old on the autism spectrum, but I’ve found that my daughter’s autism can increase her awareness at times. She makes connections that other kids her age do not, and she doesn’t feel afraid to ask blunt questions. Funnily enough, I have been asked her question many, many times.

Why are you so normal when so many horrible things have happened to you?

Sometimes what I really think people are asking is, “How fucked up are you really? Are you just hiding it better than the rest of us?”

Well, my daughter was not going to let me off the hook. She expected an answer to her question, and, you know, she deserved one. If she had the boldness to ask, then I ought to have the guts to answer her. So, I thought about it. I wanted to tell her the truth in a way that would make sense to her while also protecting her innocence. I also wanted to teach her something. This moment mattered. This is what I heard leave my mouth:

“Well, have you ever invited friends over for a playdate, and your friends just destroyed your room? They pulled books off your bookshelf, unmade your bed, broke a toy, deleted a few things off your computer that you really liked, pulled clothes out of your drawers, ate food in your room leaving crumbs everywhere, and then when it was time to leave they just left without helping you clean up the mess they made? Has anything like that ever happened to you?

Well, sort of, yeah. One of Grace’s friends did that not too long ago, and she even deleted stuff that I really liked off my computer! She didn’t even ask to use it, Mom! And she left a big mess in my room! I was really mad at her. I even asked her to help me clean it up and she just ignored me. That’s rude, isn’t it?

Yes, it is rude. So, you’re left with this big mess. You didn’t make the mess, right? But, whose room is it?

It’s my room.

Whose mess is it?

Well…I don’t know. I didn’t make the mess.

No, but the mess is in your room. So, whose responsibility is it to clean up that mess?

I guess it’s mine even though it’s not fair.

No, it’s not. In no way is it fair or right, and you can be mad and hurt and sad. You can stand up and shake your fist at the mess and yell, ‘I did not make this mess! I should not have to clean this up! This is wrong!’ But, in the end, it is your room and your responsibility to clean it–even though you didn’t make the mess. It’s still your room so you need to clean it up so that you can live in it and enjoy it. This is like me. My parents made a mess in my life when they were not nice to me. Just like some kids make messes because they were never taught how to clean up after themselves, some adults make messes in their children’s lives because their parents made messes in their lives. They’ve never learned how to clean up a mess. Some kids make messes because they don’t care. Some adults don’t care either. Some kids make messes because they’ve learned selfishness. Some adults are the same. And, sadly, there are some mean people in the world, too. Regardless of why people make messes, when a person leaves a mess behind either in our rooms or in our lives, it’s still our responsibility to clean it up so that we can live a good life. We can’t enjoy our lives if we’re living in a mess. Some people whine about the messes and never clean them up. Some people focus on the mess and learn to hate it. Their hatred becomes bigger than the mess, and they never end up cleaning up the original mess. Their hatred makes the mess even bigger! Some people blame the people who left the mess or blame themselves, but they never get around to cleaning anything up either. So, really, if you want to be healthy, you have to clean up the messes in your life regardless of who put them there without blaming, hating, and whining because, in the end, it’s your room and your life. No one else’s. We want a good life. We want a clean room. We do whatever it takes to make sure that there are no messes lying around even if the messes we find were never left by us. Make sense?

Actually, yes, that does. I understand now.”

It’s a good metaphor. It works. It is the answer to the question: Why are you normal? I’d rather substitute ‘healthy’ for ‘normal’ because what does normal mean? My normal is probably different from your normal. We all have to define what our sense of normal is going to be and go from there. After that, however, we have to get to work. That’s about as black and white as it will ever be, and I’m someone who really enjoys gray.

I meet a lot of people who don’t ever progress in their healing process because they won’t own the messes in their lives. They sit in their metaphorical rooms and allow those messes to overwhelm them. They get stuck in some kind of negative thinking be it cognitive distortions, self-loathing, blame, emotional disregulation, denial, or willfulness. They stare at the messes, point at them, and declare,

“I should not have to deal with this! I didn’t do this. Why did this happen? I’m not cleaning this up! They should clean this up! It’s all their fault! Why me? Why now? How am I supposed to do this? Am I such a terrible person that all this should be left to me to do? Am I being punished? What did I do to deserve such a horrible mess?!”

In the midst of all this negative thinking, nothing is being done. The messes are still there and, most likely, expanding and trapping us all the more. Bottom line? It’s our room. It’s our life ergo it’s our mess. Radical acceptance requires that we stop asking why or when or what if.

- You cannot change the past.

- You cannot change anything that brought you to the moment in which you find yourself right now.

- You cannot change the number of current messes in your life at this moment, and you cannot change the people who introduced that chaos into your life.

So, we accept it. We accept it all. We stop fighting our current reality and assess the damage. Take an honest look at the messes and stop assigning blame. This is really the first step in letting go of that crippling victim mentality and stepping into the healing stream.

We have to commit to cleaning up all the messes in our lives regardless of who put them there. Before you can clean them up, you have to accept that those messes now belong to you–even if you didn’t put them there. It’s your pain. It’s your injury. It’s your life. It’s your room.

We clean up our rooms even if we didn’t make the mess. That requires radical acceptance sometimes. And radical acceptance is one of the core concepts of DBT.

Welcome to DBT.

Anxiety, DBT, and The Dialectic

I have four daughters, and, for whatever reason, they are all susceptible to anxiety. Studies have shown that people born with a smaller hippocampus in comparison to others tend to struggle with anxiety and a propensity to develop PTSD after trauma. My husband has a diagnosed anxiety disorder, and he reports that he has been anxious as far back as he can remember. Anxiety isn’t just butterflies in your stomach. It can be a crippling fear that is felt all over the body resulting in symptoms like vomiting, migraines, an inability to breathe at times, and even agoraphobia.

While my third daughter has a generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), her GAD exists for entirely different reasons than my second daughter’s or my youngest daughter’s or my first daughter’s. My oldest girl becomes anxious because she is a high achiever, and she has linked her future happiness with her present achievement. If she doesn’t perform well on a math test, then she won’t get into a good college. If she doesn’t get into the right college, then she won’t get a good job. If she doesn’t get a good job, then she’ll be a bum living in her parents’ basement for the rest of her life. None of this is true. This is all-or-nothing thinking perpetuated by manipulative high school teachers trying to get their students to behave or do well on standardized tests so that government funding continues.

My third daughter has a schizophrenia spectrum disorder that developed when she was in the fifth grade. This is very rare. She is anxious because she doesn’t know if what she is seeing and hearing is real. She has experienced psychosis so she knows that it’s possible for her brain to feed her information that is false. There are times then when she asks me if what she is observing is real. Every morning and evening she shows me her medication container in order to see if she has taken her medications. She sees an empty container. Do I see the same thing? This inability to trust her own perceptions and recall of experience is what perpetuates her anxiety.

My youngest daughter has an autism spectrum disorder specifically Asperger’s syndrome. She is anxious because she is aware that there are social cues, social rules, rules that govern social behavior, and rules within interpersonal relationships, and even linguistic expressions like idioms that are supposed to be used at certain times, but she does not know or fully understand the rules or their application. She, therefore, often feels left out or excluded even after trying to implement what she has learned. It’s sort of like being the only one in a group not to get the joke–all the time. This is very anxiety provoking.

My second daughter is a very sensitive girl. She was born sensitive. When I was pregnant with my first daughter, she would stretch out as if she were lying by a swimming pool. Her tiny feet would stab me in my abdomen, and I would poke those tiny feet in an effort to get her to reposition herself. Consistent with her hard-wired personality, she wouldn’t reposition herself. She would kick me and stretch out even more. My second daughter, on the other hand, when poked would curl up and move to the opposite side of where she had previously been as if to say, “Did I offend you? I’m sorry!” She was the same as a little girl. She didn’t like crowds. I could see that she was socially anxious. She wanted to follow her bold big sister around everywhere. She liked having one friend. She didn’t like loud music. She liked Beatrix Potter, bunnies, and delicate things that she could collect. She is someone who responds to approval and verbal encouragement so when she started failing math she took in personally. When her teachers started accusing her of being lazy, she took it very personally. When she struggled to make friends in middle school while also failing math, she really took it personally. Her social anxiety began to expand and include performance anxiety around math. That larger anxiety began to include fear of her math teachers who refused to help her. She began to believe that it was useless to try because trying never helped her do better in math. Why bother? As she made friends, she discovered that they did fine in math. She decided that she must be stupid because only stupid people fail in school. That’s what her teachers implied. When she started high school, her anxiety grew into a monster. She began vomiting in school. She couldn’t even make it through the day. Where did it start? It began in the kernel of social anxiety.

Every one of my daughters is anxious, but their anxiety is very different even though their diagnosis, on paper, is the same. Why am I writing about anxiety on this blog? This topic belongs on my other blog (and maybe I’ll put it there). Well, my second daughter’s anxiety crippled her to such a degree that I had to remove her from school and homeschool her. Because I now have connections in the county due to my third daughter’s illness, I was able to get immediate in-home help for my daughter in the form of a crisis stabilization therapist who came to our home twice a week to provide us with services. The result of that service was that my daughter just started a 25-week DBT (Dialectical Behavior Therapy) Skills Group, and I am required to attend as well so I will be learning the skills, too. This is fabulous!

I’ve written about DBT on this blog in the past, and that’s why I wanted to talk about this. Many of us may have the same or similar diagnoses, but why we have those diagnoses may be completely different. Your anxiety is yours. My anxiety is mine. My daughters’ anxiety is theirs. We may be sitting in the same room together, but how we arrived there is as unique to us as our DNA. DBT, however, will be relevant to you regardless of why you require a therapeutic intervention.

So, let me just start with one basic premise, and it is the foundational idea behind DBT. It is called the ‘dialectic’. What is the ‘dialectic’? It is the notion that we can hold two opposing ideas in our mind at the same time and be comfortable with it. We can even agree with those two opposing ideas. What does that look like? I’ll use my daughters’ anxiety issues as example:

- “I can do poorly in one of my classes and still get into a good college.” Is this true? “I can do poorly in a class.” and “I can get into a good college.” Those are two opposing ideas to my daughter. This is perfectionism. “I don’t have to be perfect to be successful.”

- “I see things that are not real, but I can trust what I see.” Is this true? A person treating my daughter would say that it is, but why is this true?

- “I am failing math, but I am not a failure.” How many of us equate the event of failing with our identities? Can we fail but still be successful at the same time?

- “I am not succeeding socially now, but I will do better and learn how to navigate social scenarios in the future .” Is this true? Is poor social intelligence indicative of future social successes and even future friendships? Is this a legitimate conclusion, or not? Why?

How about this?

- “I can be anxious and still be successful.”

- “I can feel scared and still be courageous.”

- “I can be a victim of abuse and not think like a victim or act like a victim.”

And, one of the premises of DBT:

“I am doing the best that I can, and I can learn to do better.”

This is just the very beginning of DBT–learning about the ‘dialectic’. It is, however, vital that we step back and take an inventory of our thinking. Are we able to enter into the dialectical approach? Can we practice it? What are some of your ‘dialectics’?

Here are some of mine:

- “The person opposite me can be right, and I can be right, too. It doesn’t have to be win/lose. Right/wrong.”

- “I can have a ‘bad day’ as a parent. It doesn’t mean that I’m a bad parent. I can be a good mother and still have a bad day.”

- “I can have a need that is important and needs to be met, and I can still live a full life without that need being met right away or even in the immediate future. I can tolerate discomfort and uncertainty even if I don’t like it.”

Tell me what you think. Thoughts?

Resources:

The Dialectical Behavior Therapy Skills Workbook for Anxiety: Breaking Free from Worry, Panic, PTSD, and Other Anxiety Symptoms

A Visit from An Old Friend

I was cleaning my kitchen yesterday evening. My mind will wander and open up when I clean my kitchen, scrub the counters, and unload the dishwasher. It must be akin to the Shower Principle. We do something so familiar to us that our minds are free to wander into the spaces that we perhaps usually protect and even keep sentries posted over because we’re not paying attention in that moment. I think that those can be the best moments. We’ve made room for God to speak to us or even room for the other parts of ourselves to expand.

As I was noticing spots on the kitchen floor that needed cleaning, a question rang out in my mind: “Why did you never believe what your father said to you?”

That’s an old question, and I laughed about it when I noticed it drift into the forefront of my mind. My father didn’t say much to me as a child or teenager, but when he did it was usually cruel and verbally violent. Later in life when I was in therapy, I would tell my therapists the things my father had said in order to describe his character. They would always stop me in an effort to see into me. How was I? How damaged was I because of his words? How deep did his words go? I would often say, “Oh, he was full of shit. I knew that.” Sure, he had a profound effect on me, but it wasn’t his words that affected me. It was his presence. Forced association with someone like him will always affect someone. Abuse affects people. There is no way around that even if you know that they are inherently warped.

The question remained: “How did you know as a child that your father’s words were not to be believed? Children don’t usually know that. Where did you get that resiliency?”

I could never answer them. I always assumed that God had somehow protected me. He had acted as some kind of buffer, but I never understood why I never really believed my father or, consequently, his second wife who could match and exceed anything my father ever said.

I pondered that random question as I noticed stains on the cabinets. “Why did I not believe anything they said? I thought they were idiots.”

Then, a memory came to mind. It was vibrant and full-color. I was possibly four years-old. My father was still living with my mother. It was early morning, and I was in my parents’ bed. My father was sitting on the edge of the bed putting on his shoes, preparing to leave for work. I leaned over the edge of the bed and observed his shoes. Even as a 4 year-old, I was horrified, and I made no effort to hide my feelings. I boldly said, “Dad, those are the ugliest shoes I have ever seen.” He actually laughed. My father wasn’t a man to laugh easily. In some ways, this is a bittersweet memory for me. I don’t have many good memories of my father. Mostly, he terrorized me.

I sat with that memory of my father’s ugly 1970s Hush Puppies–some of the ugliest shoes ever made–and I wondered why that memory came to mind in relation to my unusual childhood resiliency. I talked to God about it. “What’s here that I’m missing?”

“You didn’t believe your father because you questioned his ability to be right. If he was wrong about those shoes, then what else could he be wrong about? You believed that it was possible that he could be completely wrong about you so you chose not to believe him.”

I laughed out loud. Really? My love of beautiful shoes contributed to my resiliency and, thusly, helped me survive a horrific childhood? That’s actually awesome.

I share this because this does relate to a broader idea. This speaks to our design as human beings. This relates to you. We are all gifted in some way. For theists, we believe that God designed us with those gifts in mind, but you don’t have to be a theist to hold this belief. You can still believe that you have a design that is unique to you that holds potential for greatness. For example, I like beauty. I’m not talking about beauty in terms of the beauty industry. I’m talking about beauty in a broader context; beauty as it pertains to nature, music, atmospheres, and even ourselves. Beauty has a healing element. It is a quality that can be pursued in life and cultivated daily. Fresh flowers on a table. A china teacup instead of a styrofoam cup. Bach for breakfast. There are ways to introduce beauty into your life that add richness and texture, and, over time, it becomes a salve that aids in healing. I was born like this. Clearly, the practicality of my father’s shoes was lost on me, but, looking back, I don’t think that’s what caused my suspicion. He never chose beauty. He never chose softness. He never called that forward or nurtured that in his wife or daughter. He chose hardness and violence, and that went against the grain of my developing identity. I knew that he was wrong, and his wrong attitudes about life were expressed in the choice of his shoes oddly enough.

You have gifts, too, and there are people you know or have known who have behaved counter to your gifts. There are people who have probably tried to steal those gifts from you or even prevent you from using them. They have treated you in such a way that may have caused you to believe that you have nothing to offer to the world. They have left you feeling robbed, violated, and defiled. That is simply untrue. You still have something to offer. You are still worthwhile, and your instincts to step into your identity should be honored. That’s where we start our journeys.

I find it so funny that after all this time I’ve learned that my resiliency originated in the opinions of my 4 year-old self. She wasn’t wrong. So, I want to encourage you to go back and reacquaint yourself with who you were when you were young. What did you want? What were you like? What were your dreams? What did you feel very strongly about? Chances are, you were right about a lot more than you realize. Begin to honor who you are now by honoring who you were. This is a vital part of healing.

Shalom…

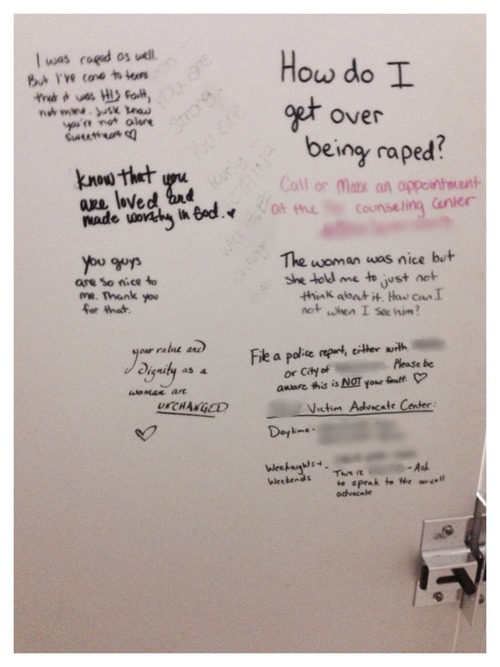

How Do I Get Over Being Raped?

Sexual abuse and rape are both topics that have been discussed on this blog. No matter how many times we are told, “You are not alone,” or “Ask for help,” or “Tell someone,” shame and fear often put a stranglehold on us, hence, hindering our recovery and ultimate healing. If there were ever proof that victims of sexual abuse do not walk the road of recovery alone, this is it. Ask for help. Tell someone. You are not alone.

‘puggitt’ wrote:

“This was in a public restroom I saw. I went in a few weeks earlier & at the time, there was only the first woman’s question on the door. The survivor’s anonymous yet public search for help & answers unsettled me, & I thought about it constantly for days. Finally, I decided I had to go back to that restroom, to that stall, just to make sure she was okay. I know, I know; it sounds crazy. But a part of me had to know that this woman, this anonymous survivor of whose identity I had no clue, was getting the help she deserved.

In just 2 weeks, this is the outpouring of anonymous love she’s received.

It does my heart so much good to see an organic uprising of support for rape/sexual assault survivors. So to you, Anonymous, know that even though we’ll probably never figure out…

View original post 44 more words

A Star Is Born

This isn’t an equipping post or an inspirational post. It’s just me, remembering something. Most of the time I simply sweep the past behind me because most of it has been so thoroughly examined and consecrated that it no longer has a sting. But this memory quietly bubbled up today as I was changing the sheets on my bed. Or maybe it seeped into my mind like a slow hiss. Some memories play out like a film. We’re standing outside the event as an observer. We see ourselves as if we’re not even an active participant in our own lives. Some memories are alive and vivid, happening to us in real time as if we are reliving them over again. That’s what this memory was like. I was suddenly thrust back in time, standing directly next to my mother as she was helping me organize my basement.

It’s funny to me because I seldom think about my mother these days. If she comes to mind at all it’s only in passing. I don’t feel very much. She’s where she is. I am where I am. We are 300 miles apart in distance, but we might as well be a universe apart in spirit. And you know what? I am finally okay with that. I grieved the loss of that relationship as if she died so it feels very surreal to me that she still lives because, to me, she died along with every dream I had that I would ever have a healthy mother.

This is why it felt all the more strange to find myself in a remembered time in my basement standing next to my mother. The memory was brilliantly clear. I remembered every detail around her presence. It was my birthday. All I wanted for my birthday was an organized basement. So, she and my stepfather drove in for the weekend, bought a plethora of organizational bins, and helped me take things out of the cardboard boxes and put them in plastic bins. My stepdad organized our tools, installed some lights, and built some shelves. I was just happy to have the task finally underway. It had been weighing on me. As is my mother’s way in all things, no gift is given freely, and I am never allowed to expand into any sort of identity that might threaten hers. This is how her borderline personality disorder is expressed. She will try to be generous, but she must always take a pound of flesh in exchange preferably at a vital spot that might cause longterm damage.

I recalled that I was organizing the newly built shelf. I was happy. She saw that I was happy. She came alongside me and commented on my basement.

“It’s coming along nicely.”

“Yes, I’m so happy. Thank you so much. This was so helpful.”

“Well, don’t think you’ll be getting anything else from us for your birthday. I think that this is quite enough, don’t you?” she remarked with a hardened smile.

Stunned into silence, I nodded.

“Well then, I can tell you that this looks nothing like our house. It sure is beginning to look good after all that renovation we’ve been doing. Granted it was a mess after taking down those walls, and I didn’t like it. All that dust!” She then turned to me with a haughty expression and quietly said, “But I’ll tell you this. You would never have been able to handle it.” She then tossed her hair and continued organizing the shelf as if she had just told me that she liked my haircut.

This is standard behavior for my mother. She’s like a scorpion. As soon as you feel like you understand her or even feel comfortable, she’ll get you from behind. My training would have dictated that I say nothing to her after a sting like that. Granted, that’s tame for my mother. She was just being herself. In her eyes, she is the Queen. She gives happiness. She is the provider of all good things. If I seem just a bit happier than she intended, then she must take it away as a reminder that I am her subordinate always dependent upon her for everything. In this case, however, I didn’t want to submit. I didn’t want to remain silent. I didn’t like the sting. So, I spoke up.

I turned to her and said emphatically, ‘You have no idea what I’m capable of handling, Mother.”

She was so surprised by my response that she stumbled backwards and fell. I did not help her up. She glared at me. I knew I would pay for it later, but I didn’t care. I was an adult.

When I remembered this today I felt an urge to cry. Then, I felt another far baser urge. I wanted to find my mother and shove her face in her own shitty declarations and yell back, “Do you see? You were wrong about me! Do you see? I’ve handled you! I’ve grown up and become a far better person than you’ll ever be! Do you see? I am raising my daughters under extraordinary circumstances, and they are great kids! I’ve been married for nineteen years! I’ve done this in spite of you with all the hurdles you’ve thrown in front of me! I don’t need you. I don’t need your approval. I’m doing just fine! So there!”

And then I felt guilty for feeling that “carnal” urge to shove my mother’s face in her own abusive shite. I sat with my feelings for a moment, picked up my newly covered pillow, and sniffed it. It smelled clean and fresh, and that comforted me. It was also cool against my cheek, and I have a thing about cool pillowcases. I had no idea why I had remembered my mother’s toxic words today. I try to pay attention to memories when they come forward. They speak to us. My mother often told me that I wasn’t good enough. She had to impose her own self-loathing on me through words and violence. As is typical for her expression of borderline personality disorder, she could not permit me to separate or individuate. I was never allowed to be. I was only allowed to do particularly what she forced me to do.

I think it’s why I can let this memory pass on with the rest of them and release my mother from yet another debt. Ten years ago, this memory would have hurt me more. Today, I see her more clearly because I see myself more clearly. I can do today because I am, but my doing doesn’t define my being. If I fail, it doesn’t define me in any way. My being is already settled. I in no way loathe who I am. I don’t feel empty or rootless. My mother can’t agree with any of this. One can’t give what one doesn’t have.

Standing in my basement, my mother did indeed fall. She lost her place of power over me because I spoke up. Maybe that’s why I remembered this moment today. Maybe it’s not her words that I was supposed to recall.

Maybe I was supposed to remember mine.

“You have no idea what I’m capable of handling, Mother.”

Maybe you have some memories that bubble up and sting you, too. Maybe you’re not seeing what’s really there. Maybe you’re a helluva lot stronger than you know.

If I was really the star of my story that whole time, and I just realized it now…then what does that mean for you?

Learning to Deal

In my last post, I talked about learning to make plans for yourself in the context of possessing a sense of a foreshortened future. This can feel almost impossible if one has poor distress tolerance. Distress tolerance is very important when it comes to learning to make plans for the future because it’s our ability to trust our own resiliency that enhances our self-esteem and gives us a sense that we can overcome present and future challenges.

For example, I used to have very low tolerance for disorder in my environment including loud noises. Well, don’t have children then, I say to my past self. I would feel very marginalized and overwhelmed when loud people entered into my home. I really liked to be hospitable, but I would become very anxious upon seeing a messy kitchen. When my children got old enough to ask for their pre-school friends to come over and play, my initial reaction was one of horror. Another child? In my house? I would consent because I wanted my kids to have fun, but I hated every moment. I felt adrift internally, out of control, and invaded. My environment was too loud, too messy, and disordered.

Why was I like this? Well, I grew up an only child until my mother remarried when I was 11. I was also a latch key kid beginning at the age of 7. I spent most of my young life alone. I’m also an introvert. When I experience stress, my first coping strategy is to seek time alone. My next coping strategy is to clean because cleaning gives me something to do while I process my emotions. When my mother remarried, however, my quiet life of solitude changed. I had two new stepsisters who were both older than I, and my mother’s marriage to her husband can only be described as “nuclear”. The fighting was epic. If you were to watch the movie “War of The Roses” with Kathleen Turner, you might get a sense of what went on in our household for seven years. My stepsisters and I cowered in our bedrooms most of the time hoping that an object thrown in the heat of the moment would not strike our heads. Sometimes it was just so absurd that we emerged just to eavesdrop. Sometimes the cops showed up because a neighbor had complained. I was either terrified or amused at that point. We were that family.

So, as an adult, I had almost no tolerance for normal expressions of frustration, anger, or negativity. If someone looked at me sideways, I would start trembling, and then I would start cleaning something. Must exert control over something. Clean something! Anything! The healthy part of me would speak up and tell me that this was no way to live. I didn’t know that what I was experiencing was anxiety. I didn’t know that it was rooted in PTSD, an anxiety disorder. I didn’t know that I needed to increase my distress tolerance. I just knew that I needed to learn to relax. I needed to learn to leave messes for a while in exchange for some fun, but I had never done that before. I was not allowed to do that growing up. Ever. Growing up, if I left a dish on the counter or, God forbid, crumbs, my mother would lay into me like I had just driven the car through the garage door. If I left streaks on a window or mirror after cleaning them, she would make me do every mirror and window in the house for good measure even if they were already clean. I once attended a birthday party at my next door neighbor’s house. I chose to go to the party first rather than clean my room. I was going to clean my room afterwards. My mother came to the party, humiliated me, and made me leave early because I had not cleaned my room before going. We were not allowed to do anything, enjoy anything, or have fun unless we had met her standards for cleanliness, and her standards were military. She even did the white glove test on my bedroom furniture and once bounced a quarter off my bed to ensure I had made it properly.

I’m not sharing this to vent or garner sympathy. The reason I put this out there is because low distress tolerance exists in people for a reason. Human behavior originates in something. My former inability to enjoy life. filter out the background noises, and deal with a certain amount of environmental chaos was really tied to a tremendous fear of my mother. I was programmed. When I made a point to deal with the root issue, my mother, my distress tolerance for the troublesome environmental factors increased. I began deliberately exposing myself to the very things that caused great anxiety in me. I invited my daughters’ friends over. They made messes. I made myself sit in the discomfort of it. I increased my distress tolerance. I deliberately left crumbs on my kitchen counter. I didn’t make my bed. I even left streaks on the mirror in the bathroom. I made myself miserable so that I could teach myself that I could be highly uncomfortable but functional at the same time.

In my mind, this is the heart of distress tolerance. I work with my daughter on this very idea almost daily. I ask her questions like:

- Can you feel sad but function at the same time?

- Can you hallucinate, know that what you saw was a manifestation of your brain misfiring, feel anxious about it, but still go on to function?

- Can you feel very irritable to the point of wanting to act on it but still choose to do something functional with your body while feeling that feeling?

Tolerating unpleasant emotions does not mean that we accept or justify what caused us to feel that way. I don’t justify my mother’s behaviors. I don’t accept them as life-giving or even good. I do accept, however, that I feel the way I feel. I accept that I don’t like how I feel sometimes when I’m reminded of what I experienced growing up. I also accept that I can feel a negative feeling and still be functional. I don’t have to say, “Nope. Shutting it down. I can’t deal with this.”

What if I can deal with it? What if it’s just so uncomfortable because I’m not accustomed to sitting with it? What if I don’t trust myself to handle it because I was never allowed to feel anything in my former environments? What if I was always told that how I felt didn’t matter? What if I was told that feelings were opinions, and my opinion was stupid? There are a plethora of things that we might have been told that prevented us from realizing our own resiliency, but it doesn’t mean that we accept them as truth. It also doesn’t mean that we can’t begin practicing now. We can, at any time, give up the line, “I can’t deal with this,” and replace it with, “I will learn to deal with this.” Once you change your mindset from one of helpless victim to empowered and learning adult, the world opens up to you. Maybe you won’t like your choices, but it doesn’t mean that you don’t have them.

Yesterday, I had a choice. A family member emailed me–AGAIN–wanting information about my mother. I’ve explained to this person more times than I should have to that I’m not in a relationship with my mother. I don’t want to give too many details because I don’t want to discuss my mother with her. I have never desired to vilify her. Suffice it to say, if an adult child tells a family member that there is no relationship, that suggests that there are problems. Be respectful for goodness’ sake! Don’t keep asking me if I’ve talked to my mother! Don’t you understand what feelings your lack of empathy provoke in me? There is, however, never understanding. So, I get emails that say things like this:

It sure would be nice if I had a picture of you and the girls to show your mother when I see her next month.

I’m not a fan of the passive approach. Just say what you mean. Embedded in this statement is a request that I send her a photograph of my family so that she and my mother can discuss me. Nope. Not gonna happen, and I told her as much. She is getting in the way of a process that has been set in motion. One that has the possibility of actually doing some good. When people begin to interfere, believe my mother’s distortion campaigns, and attempt to force reconciliation, I pay a very high price usually in some form of retaliation. I won’t endure this sort of behavior anymore.

How we bounce back from interactions like these tell us a lot about our distress tolerance. When I read that email, I groaned aloud. I complained to my husband. I emailed my family member, and then it was over. I emotionally moved on. It was contained. No crying. No panic. No cleaning rampage. Alright, I might have said something about someone having the emotional intelligence of a sea anemone. Otherwise, it was handled. I did not say that I couldn’t deal with it. On the contrary, I said, “Good grief, now I have to deal with this!” Take note, however, that my language described my capabilities. I can deal with this even if I don’t want to deal with this. Not wanting to do something is very different from not being able to deal with something.

Distress tolerance. It’s something that every person on the planet needs, and every day provides us with an opportunity to practice it. Once you begin to believe that you have what it takes to tolerate varying degrees of distress, you are that much closer to being able to imagine your own future. Why? Because if the future is scary to you but you believe that you’ve got what it takes to overcome scary and distressful situations, then you’ll have the resiliency to begin taking risks. And making plans about a future that you know nothing about? Really, what’s riskier than that?

Looking Ahead

I don’t know to whom I need to attribute this image. It’s one of those images that gets passed around Facebook and Pinterest, and everyone LIKES it. It feels inspirational. It seems like something one might hear at a political rally or in a stump speech. There’s a reason, however, why this image and its embedded statement move people. There’s a reason why people who have been traumatized or profoundly wounded read this and feel…weird. Perhaps excluded. Like something about the idea of having a vision and future doesn’t really apply to them. It feels like a romantic or fanciful notion that Anthony Robbins preaches to extort money from emotionally impoverished people who are easily manipulated. A vision. P’shaw.

But, if you have been victimized in your life, then sit back and try imagining where you might be in five years. Ten years. Twenty. Can you do it? Can you see yourself accomplishing what you’ve always wanted? Can you financially plan for it? Are you able to imagine your own future? In color?

I can’t.

I know some people who can. I’ve met people who really get into the whole Let’s-Write-Down-Our-Dreams-For-Our-Lives thing. They really bond over talking about the future and their vision of it for themselves. They are, in fact, visionaries. They love “dream” talk, and they love listening to motivational speakers who are very future-minded. Their eyes are always on the horizon. I wish I were like this. I’ve never been able to conceptualize the idea of The Future. I thought I was just strange. I ran away from the motivational speakers in high school. I avoided all discussions of the future aside from what could be done in the now. I didn’t know why I was like this.

I do now.

It’s called a sense of a foreshortened future. I’ve written about this before, but it’s a topic that’s important to discuss because it impacts every area of our lives. It’s a lesser known symptom of PTSD. Why? Because acute symptoms of PTSD involve hypervigilance, startling easily, nightmares, and flashbacks. Once those symptoms fade people often think that their PTSD is healed or in remission, but what about this sense of a foreshortened future? That doesn’t really describe an acute symptom of PTSD, does it? No, not really. How does something like this develop? Well, think about trauma and how we cope. We are exposed to something that our body and brain view as a threat to our survival. When we are trying to survive we are only concerned with the moment. We no longer think of the future. We no longer plan. There is no point to planning beyond the next few moments because the point to surviving is living through this present danger. The nature of PTSD is that we are fooled into believing that we are still stuck in a dangerous situation. Our ability to plan or even look ahead is disabled. How does this manifest in real time?

I can only speak for myself really without citing academic articles. My plan during adolescence was to get away. I had to survive high school and go to college so I developed tunnel vision. I stopped encoding a lot to memory during my teen years simply because I had my eyes on one goal–get away. Far, far away. I had to work my ass off to earn a scholarship and leave everyone behind. I have only vague memories of high school all of which are mostly unpleasant. I do remember the violence in my home. I remember the trauma. That’s in Technicolor. That’s what motivated me to work. My time in captivity is almost in black and white. The days just blur into each other. Even then though I knew I had to get away. I was, of course, terrified, but I was almost equally pissed off that I had worked so hard to get away from the horrors of my family of origin only to end up with a human trafficker. I wasn’t going to go out like that. I had to go to college. That was my goal. That was my vision. College. I had earned it. That’s what helped me overcome my paralyzing fear in captivity. I was, I guess, sort of pissed off that I was being kept from reaching my goal.

When I did finally graduate from college I stopped functioning well. I did not know why. For years, I never understood myself. I had done extraordinarily well in college. Many doors opened up for me in the academy. What was wrong with me then?

Well, due to a sense of a foreshortened future I had only ever been able to see my future as far as college graduation. I never believed I would live beyond that. I could not plan for or envision my life beyond Graduation Day; hence, the existential crisis that followed. I was not able to manage money. I was not able to feel grounded. I was anxious all the time. I was not able to practice self-care beyond what an adolescent might do. I was flaky, self-absorbed, and extremely insecure simply because I lacked ontological anchoring. When you believe that your life really has no future, co-morbid disorders crop up as well like Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD). Anxiety disorders are common where there is a sense of a foreshortened future particularly OCD because a need to be in control of, well, something is so necessary. The more control one can have the better. I used to have OCD to the point that I couldn’t leave the house unless all the tassels on all the area rugs in my house were perfectly parallel to each other. I would not be able to sit still or focus on anything unless they were perfectly straight. If there was visible dust on anything in my house, I would feel panic. If there were crumbs in between the couch cushions, I would panic. If the top sheet on my bed was not put on just the right way, I couldn’t sleep in my bed. I would wake my husband up just to fix it. I drove myself crazy trying to keep something in my world orderly because I had no sense of control anywhere else.

Eventually, I just fell apart. I didn’t want my daughters to follow in my footsteps so I began dealing with my OCD issues by leaving the tassels on the rug askew. It was like being tortured. I made myself only dust once a week as opposed to daily. Panic! I wouldn’t allow myself to even look in between the couch cushions except on Fridays. Only then could I vacuum. And, I’m not allowed to wake up my husband to adjust the sheets. I just have to live with it. Oh, the pain! But, I did it. I even leave crumbs on the carpet now…for a few days! Victory is mine! This triumph over my anxiety has come, however, with addressing my lack of vision about my own future.

I still can’t see or envision having a future, but now I know why. And, I know that it’s reasonable. I survived a murderous psychopath who not only tried to sell me but also threatened to kill me! More than that, I tricked him and got away! And then there’s my family of origin…

We have to give ourselves credit for all that we’ve overcome to get where we are. We are going to be scarred. I may not be able to envision my own future, but I have people in my life who can. This is what love means. We find those people and ask them what they see in our futures. We ask them to be seers for us. Dream for us. Think big for us because our imaginations are too small where our own lives are concerned. I can see to the top of Mt. Everest for so many people. I can see all the way to the bottom of the Marianas Trench even, but, when it comes to my own future, I get stuck. I look in the mirror sometimes and I see the words scrawled above my head, “The girl who got away.” Even I know that this is not good enough. It’s an identity rooted in the past, but my brain’s been traumatized. I need help sometimes.

For you, it’s okay if you need help, too. It’s completely normal if you can’t see your own horizon or even the next few steps that everyone else can see except you. It doesn’t mean that you’re weird or stupid or an outsider. It just means that your brain developed differently because you were wounded along the way. You experience time differently than others whose brains weren’t exposed to trauma. It also means that it’s important that we ask our trusted allies for help in this area because we do need vision in life. We need to know in our knowers that just because we can’t discern a future or dream a big dream or hold tight to a big, fat vision doesn’t mean that one or two or five don’t exist for us. It just means that we haven’t crossed that threshold yet, but we just might. And until then, keep asking the people who love you what their dreams for your life are because the last thing we want is to be rooted to our pasts particularly when our futures are quite possibly so good.

‘For I know what plans I have in mind for you,’ says Adonai, ‘plans for well-being, not for bad things; so that you can have hope and a future.’ Jeremiah 29:11

For Further Flourishing

I nearly dropped my cup of coffee this morning when I saw the Rainer Höss had commented on yesterday’s post. I choked out a loud, “Holy crap!” As it turns out, Rainer has a website and Twitter account, and he, too, has written a book. So, I thought I might put together a list of all the books I mentioned in yesterday’s post as well as the authors’ social media in case anyone might be interested in reading or following them. I am still trying to figure out if Rainer’s book has been translated into English yet, but his website is translated into English and very nicely done; his Twitter feed is in English as well. Please do go check it out.

- Rainer Höss, Das Erbe des Kommandanten (The Legacy of The Commander), website, Twitter

- Katrin Himmler, The Himmler Brothers: A German Family History

- Monika Hartwig, Inheritance (2006 documentary)–this film can be found on Netflix, and it streams for free with a Prime membership on Amazon.

- Niklas Frank, In The Shadow of The Reich, Der Vater, Meine Deutsche Mutter, Raubritter: Das Erschröckliche Und Geheime Leben Der Heckenreiter Und Wegelagerer

I didn’t mention Niklas Frank in yesterday’s post simply because I didn’t want the post to become too long, but he has written a few books. He is also a public speaker. He speaks to youth throughout Germany from what I can tell. There is, however, an amazing scene in the film between Frank and his daughter. It is not to be missed. If there are any of you who have made sacrifices in the way of cutting off family members in order to create a different life for your children, then you will want to watch this film simply to hear what Frank’s daughter says to him. It is moving and redemptive.

It is important for people in recovery of all kinds to look at the lives of others who come from difficulty but live successfully. How have they done it? How do they flourish in spite of the fact that their beginnings were not ideal or possibly even extreme? Reading one another’s stories can inspire us to continue to put one foot in front of the other even on the hard days. It also pulls us out of our own self-involved orbits.

We need each other.

Let me know what you think of the suggested media if you read or watch them. If you speak German, you’re gold!